Stools are often referred to in old English as both "stoole" and "form". I am curious to know if it was called a 'form' because sitting in one would doubtless help one maintain a good 'form' of seating posture, as it would be hard to slouch whilst sitting on one, but I have not found any definitive information to support that notion. The doctor has further confused the meaning of "stool", because when he asks me for a sample, he does not expect me to bring him back a piece of furniture; though again, that must originate from the fact that there was once a "close stool", which was a chair with a pot in the seat...

|

| A stool and other furniture depicted in the late 7th century Codex Amiatinus |

In a previous post, we already discussed plinth chairs; these are not stools, even though modern readers might think of them as such. In defining a stool, we are using, here, the definition of a form of seating with a seat and an open base, as in, not a box or other solid, enclosed structure underneath. Generally, if it is not at least partially open beneath the seating surface, we will not be classifying it as a stool.

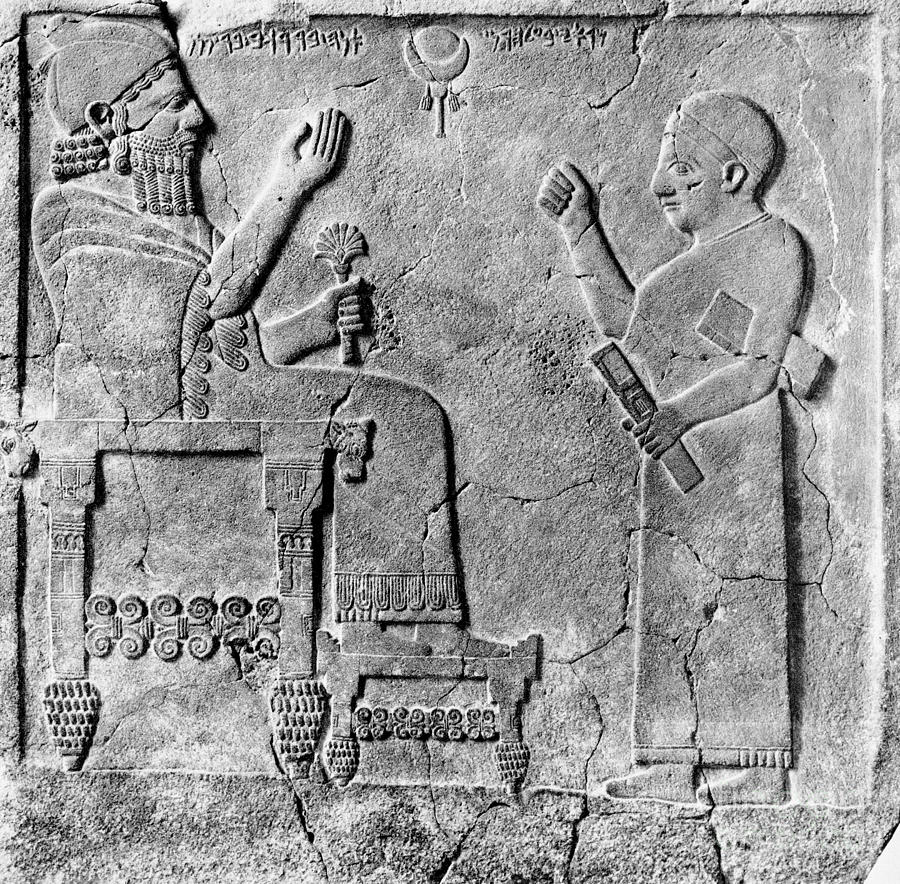

As with other types of furniture, I like to give a bit of pre-medieval history on the topic so one can see where the medieval pieces fit into the long evolution, and also to show how styles may have, (or not) changed. With that in mind, below are three examples from some of the ancient civilizations that influenced and affected the Roman and subsequent medieval European furniture.

|

13th century BC Stool from the Cairo Museum

(picture found on a Google image search)

|

|

| 9th century Hittite sculpture depicting a king seated on a stool (picture found on a Google image search) |

| Portion of the Acropolis freeze from Athens; 4th century BC showing four figures seated on stools (From Wikipedia) |

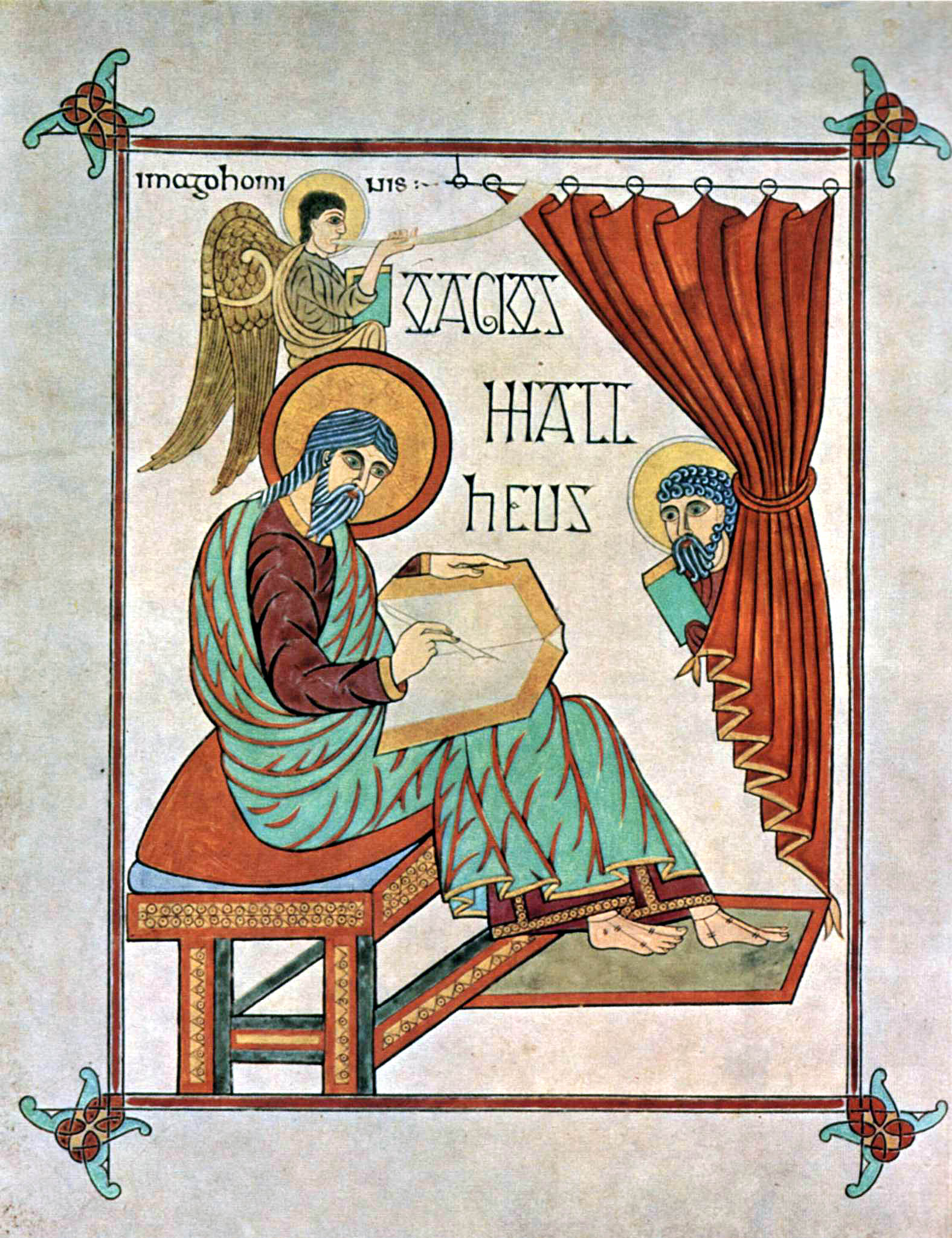

The Illustration at the beginning of this post featured a stool from almost the very onset of the Middle Ages, and in construction details, is not unlike the Hittite example which was already 2,000 years old at the time that the manuscript from which it comes from was made.

All of these stools fall into the category of four legged stools, but there was also another type, which was a folding "X" type. This design too, has a very ancient pedigree, and examples are found in Egyptian, Minoan, and Greek art. In addition, we have many examples of bronze Roman era stools of this type.

These folding stools could be constructed of wood or metal, and were found throughout Northern Africa, the Middle East, and all parts of Europe. There have even been several BC era wooden examples recovered from graves and peat-bogs of northern Europe. I will not get into more details on this topic because the St Thomas Guild blog has already covered this form in great detail. You can read more about the medieval varieties on their blog. I will add this one example, however, from a 9th century manuscript, because they did not discuss metal varieties of this chair, several examples of which also exist.

|

| BNF Lat. 17968 fol 125v; depiction of a folding iron stool from the 9th century |

Having gotten that bit out of the way, there is still a huge variety in the style, methods of construction, and level of ornamentation of the fixed leg stools. It would be impossible to give an exhaustive synopsis of even all the known examples of depictions covering an entire continent and a thousand years of history, but even if we did, that would only be a fraction of what was actually produced, as so much has been lost to the ravages of time.

When one considers history which is hundreds or thousands of years old, he must first accept that whatever he gleans in information is a pale reflection, at best, of the vivacity and variety of actual life in those times. A word, a phrase, an illustration, all give us tantalising hints, but hints are all they are, and must be regarded in that light.

Those hints tell us that there were three four and even five legged stools. There were stools with carved and sculpted ornamentation as well as others which were of the turned variety. Still others were constructed of flat timbers which could be left plain in form, or decorated by shaping and or carving. As in all other types of furniture, peasants and poor people would have simpler versions than their financially more fortunate compatriots. Since medieval artwork is almost always primarily concerned with the general shape of an object, not its exact appearance, this is not always readily discernible to the modern viewer of such artworks.

Below are some examples of various stools taken from different periods of medieval history, but are in no way intended to suggest that any particular design was circumscribed to that time period. I have one illustration for each of the centuries comprising the millennium, known to us as the Middle Ages. I have shown a variety of styles of construction as well as a wide range in ornament, detail and material. (the 7th century is represented by the first illustration in this blog-post)

|

| St Mathew from the 9th century Lindisfarne Gospel; Mathew is seated on a wooden stool decorated with carved ivory panels. (at least that is how I interpret this) |

|

| From an astronomy manuscript in the Bavarian State Library (BSB clm 210 fol 118r) produced in the year 818 This shows a turned stool with legs which extend above the seat and have knob type finials. |

|

| BNF Lat 6, fol 5r 10th century |

From the Bibliotheque National de France, comes this small illustration from a 10th century Bible. This is a scene from the story of the life of Samuel; in this scene, the Prophet Eli has just been informed of the wicked acts committed by his two sons, Hophni and Phineus. In shock, the prophet falls backwards off of his chair, here depicted as a seat with legs fit from the underside, perhaps in a through tenon joint, like those found in many 16th and 17th century English stools, but also depicted in 14th, 15th, and 16th century artwork.

|

| Nativity scene Detail of one of the Salerno Ivories from ca 1080 |

Here is another turned four legged stool, but notice the degree of ornament suggested in this example. It seems to have a square terminal above the turning where it joins with the seat. Something I would like to point out in this illustration is the way the bed was depicted. The artist wished to show the turned posts for the bed corners, but had he put them where they belonged, from a realistic point of view, they would have been obscured by the bed itself and the figures, thus he chose to depict them seemingly propping it up from underneath, stool fashion. This is a classic example of why we cannot take medieval illustrations at face value; they are simply conveying some information, but are not "photographic depictions". Notice also the little tripod table.

|

| 12th century relief with Madonna and Child |

I could be wrong, but I believe this is in the Louvre, there is a similar one in the V&A, but the stool in that panel has round legs whilst the panel itself is rectangular. In both cases, the seat seems to be constructed of very massive timbers with a lot of carving. I would expect these to be made in a way much like the still existing 12th and 13th century choir stalls; very thick, solid timber.

|

| Another Madonna and Child, this one from the 13th century |

Remember the 9th century stool with knob finials? This is a 13th century version of the same basic idea. I think this is from the Met in New York, but again, I am not 100% certain.

|

| Late 14th century Stool "from a Museum in Paris" Part of the stretcher and its carving is missing. (picture found on a Google image search) |

b

|

| St Luke. BL Yates Thompson MS 4 fol 14r ca 1460 |

Notice the similarity of this drawing and the actual example from about 100 years earlier pictured above.

Furniture obviously evolved and changed over time, but some of the basic fundamental forms persisted for centuries, even millennia, as with the 'x' stool and the three corner stool. Often these forms are obscured by the various decorations that did change with fashion and taste over the centuries, if you examine them from a construction standpoint, though, they remain much the same. It is too bad there are not more pattern books preserved from the Middle Ages, as they would help us a lot in knowing how artists and craftsmen went about ornamenting their wares. Without such knowledge all we can do is study other decorative objects and guess.

Hopefully this post gives some idea of the vast possibilities that exist for this type of furniture and shows that it was something much more than just a simple plank or turned object usually depicted as "medieval" stools. (Just try doing a google image search for "medieval stool" and see how many of the examples I have given here are represented.)

Videre Scire