I n previous posts I have introduced my "Millennium Box". In the beginning it was not so named because I had expected it to take that long to finish, but because it is supposed to be patterned after the art of the "turn of the millennium", as in circa 990-1010 AD. My first post, after completing the construction of that box was 12 November, 2017; an unbelievable quick three years ago.

|

"Turn of the Millennium" 10th century box,

front detail |

I have always been an artist, and have been painting since I was 12, but I had to learn to paint all over again to work on this box. My intent, from the conception more than three years ago, was to crate an expensive painted medieval box, and I had even worked out the theme, some of the designs, and had begun to purchase authentic pigments for executing the plan. The idea was to not only paint it with art inspired from late 10th/early 11th century manuscripts, but to do it with egg tempera, one of a few different options available to a turn-of-the-millennium artist.

|

The box with a new coat of gesso. The top has been

scraped smooth but the sides are still unfinished. I used

a cabinet scraper for the flat areas and a file to trim up the

rim of the box and give tiny chamfers to the corners. |

There were several factors that caused the process to take three years, one of them being that after I finished making the box, I covered it in gesso and then left the country for six months to work on a job. When I returned to my workshop, I found the gesso on the top had cracked. Somehow, the fabric that I had put on the box prior to the gesso, (as per Theopholis' instructions) had not adhered well, and it seems that there was also a bit too much glue in the mix. Whatever the cause, I had to remove everything from the top and do it over. I had also made some "gesso sotile" following the instructions of Cennini, and that was put over everything and scraped down after I had repaired the top.

The second, and even more fundamental reason for the delay, was that I had to mentally get myself ready to do the painting. I had never made or worked with egg tempera before, and there are so many factors that come into play that made it a bit daunting to commence. Once I finally spent enough money accumulating pigments, and had read, ad nauseum, the medieval treatise available to me on the subject, it was actually time to stop baulking and get to work.

|

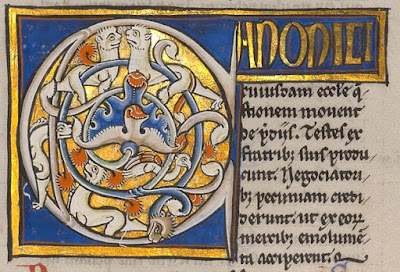

| BNF Lat. 9448 fol 54v and 73r ca. 990-95 (cropped) |

As I mentioned, my idea was to make a box with a theme, specifically my own zodiac sign of Leo. I also wanted to incorporate the Sol and Luna (sun and moon), which was a popular, oft repeated theme, in medieval art. As with medieval artists, I would chose my subject mater from the images available to me, and adapt them as my artistic skill and inspiration allowed, to come up the with figures to fit my intended theme. I had seen several examples of the sun and moon personified as king and queen, but all of them were only bust or half length figures. I wanted full figure seated persons, and so adapted figures which were originally other characters. These images came from a manuscript produced in Prum Abbey (Northern Germany) around 990-95 and are now housed in the BNF. (French national library) My second source comes from a manuscript now in the Boulogne-sur-Mer branch of the French Municipal Library, which is a late tenth century copy of a 9th century copy of a now lost, but probably Roman original. The extant 9th century copy is known as the Leiden Aratea. There are scores of surviving medieval manuscripts which point back to this model.

|

Some of my drawings for the design of the box. Changes

and adaptations were made as I went along, but this was

a starting point. Nearly all peripheral decorative elements for

the box were taken from the Prum Abbey manuscript. |

One must always bear in mind, when it comes to art, that an artist needs images to work from, and he will make the best he can with those he has access to. A well paid and traveled artist would be able to visit many libraries and source an abundance of imagery, but a less-well-off artist would have been more limited, and thus need to rely more on his imagination; the resulting work would probably be viewed by modern eyes as more "crude" or "primitive" looking. There are hundreds of examples of medieval art which clearly show that one artist had access to another work, or indirect copies thereof.

For my box, my imaginary medieval alter-ego had direct access to both of these primary sources; his own artistic ability took those models and made an original work of art to suit his patron's requirements, as was the practice of every medieval craftsman. One cannot begin to stress enough, the difference in the creative process that would have existed in a world without the photographs, printed images, and magazines, not to mention all of the digital media, that we now take so much for granted. Copying was not seen as a sin, but as an essential element for creativity. Everything that we have, owes its existence to all that came before.

|

Boulogne-sur-Mer, Bibliothèque municipale,

MS 0188 Fol 32v sp. 10jh (cropped)

Sadly, the 9th century version of this image has been lost,

it would be interesting to see what changes had been made by

the 10th century replicating artist.

|

Having gotten all of my images together and planned out, I was still not quite mentally ready to tackle the job, so I decided to ease myself into it by painting the inside of the lid. Most boxes of this calibre would have had cloth linings, but I reasoned, that it would be difficult to line the lid, given all of its angles, with a piece of fabric, and if I did so, the pattern on the fabric would necessarily have been almost completely obliterated, thus it would make more sense to paint simulated fabric where the pattern could be "bent" to give the illusion of following the contour of the lid but maintaining a discernible design. My pattern is a combination of two ornamental garment designs found in the Prum manuscript.

|

| The extent of the "practice" that I did prior to beginning the lid |

|

This illustrates most of the process of egg tempera.

The dry pigment is "ground" with water to give it a "paint"

consistency, the colour is then transferred to an authentic

medieval "paint cup" (shell) and mixed with egg yolk,

itself tempered with water and vinegar. |

|

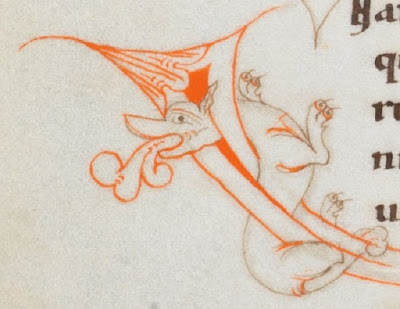

As in my model manuscript, most design elements were not

drawn out beforehand. The artist just started out and whatever

happened is what it was. This, in my opinion, lends

to what I see as the natural beauty of medieval art. Not

over-thinking and over-planning. The results look more

spontaneous and natural. They are perfect in their

imperfection |

|

A "red" colour, and the components used to achieve it.

On the green background it looks much more like red |

One of the challenges that reared it head almost immediately was getting the desired colours from the dry pigments. As soon as water is added, the colour changes. The relative colour also seems very different on a white box than it does on my black granite grinding slab. Most of my painting career has been in oil, and I have always had a white or light wood-coloured (maple) background on which to mix it. The medieval manuscripts on painting recommend a "porphyry" slab for grinding the colours. Porphyry is rather purplish red with white spots, and though light, is certainly not white either. I did not have any porphyry in the first place, but this granite slab seemed a good substitute. Learning to judge the finished colour on a black background took a lot of "trial and error", (mostly error) however.

|

| The finished inside of the lid |

Even the border decoration was painted without prior drawing. I did put a dot of white paint at the point where each curve reached the edge and then started connecting the dots. Somehow I got one more repeat of the pattern on the lower edge than what I had on the upper.

|

After finishing the inside I was finally ready

to take on the outside. I began at one end and

painted the border to completion.

|

I then realised that I should be painting everything in stages as I went, colour by colour. This would serve two purposes, first, the whole box would be more harmoniously decorated, and second, I would not have to be constantly re-mixing the same colours.

|

With that Idea in mind, I began the entire box as a single

unit. |

One problem with that plan, however, was that I had never finalised the design of Sol and Luna for the front of the box. I had to stop and do that. Once they were drawn, however, I spent more time working on the front at the neglect of other panels, so the idea of mixing each colour only once did not really work out very well.

|

| Starting to show some real progress |

|

At this point, I felt a sense of actually "getting it"

|

One frustration that I encountered was in attempting to replicate the colour purple. I had purchased two different "purple ochres", but neither one of them came close to the purple of my Prum Abbey model. I also had purchased several "reds" and "blues" which were supposedly what "was available" to a 10th century European artist, but no amount of mixing of any of them came close to achieving the desired colour. In the end, I had to do as any other medieval artist would have done, and content myself with what I had to hand. The bold use of purple in this 10th century manuscript is almost taunting however, and it seems, in looking through the entire volume, as if the artists (there were at least 4 working on this) after having gotten hold of some purple, were able to refine its colour to greater advantage as they went on, and made more flamboyant use of, and greater glee of having gotten hold of it. I would really love to know what their source of pigment was!

|

A brilliant "true" purple from the Prum Manuscript

By comparison, my purples are hardly purple at all |

|

At this point I am more than two weeks into the process,

Using every minute that I can carve out for the purpose |

|

The next big transformation

came when I began adding

details |

|

The details were fun and why I so loved this particular

manuscript in the first place.

Painting parts of a single pattern in different colours was

"a thing" in 9th, 10th and 11th century art. |

|

The end where I began wound up being the

last to be finished. The horses were a bit

mentally daunting for some reason. |

|

Sol in his Quadriga rides across

the sky, bringing light to the world

Krebs, or Cancer, is on the left lid end as he is

the sign before Leo. |

|

Abstract stars and clouds in a night sky for the back panel

|

|

Textile inspired designs make up the back, as was a very

common practice with medieval Chests, boxes &c.

|

|

Luna lumbers across the night sky in her ox-cart.

Virgo, holding Libra, a common means of depicting

both signs together follows Leo as the year advances. |

|

After some 80+ hours of work over a period of one month,

The box is finally finished. |

After putting away all my pigments, and cleaning up and stowing all of my equipment, I realised that I had forgotten to paint in the scepter which was supposed to be in Sol's hand. I just did that this morning as can be seen in the first picture at the top.

|

Finished, including the 23K gold-leaf accents, but not without

the scepter - This would never due. |

In all, this has been an educational, interesting, and fun project. If I could do it again, I would make some changes, but I feel fairly happy with it. Most important, however, is that it achieves its original goal of demonstrating the possibilities and potential beauty of the millions of lost objects from the earlier centuries of the Middle Ages. We have many examples from the 14th and 15th century, but these hardly reflect an entire millennium of artwork, nor do they illustrate the complexity and skills which early artisans had in the so-called heart of the "dark ages"! This box, then, is a slight attempt at demonstrating that reality.

Still to come will be a set of cast bronze feet to stand on, a lock to secure the contents, and a ring-handle by which to lift or carry it. I wonder how long it will be before that part is finished...