|

| St Luke, from a Gospel Book, 3rd quarter 9th century A very classic example of the plinth chair |

In the first part of this article, I mentioned the pre-medieval origins of chairs in general. There is also evidence of the plinth chair from the classical world, but we find an interesting twist to the subject; there are very few portrayed in the Roman period. I have seen Greek and Egyptian examples in their respective artworks, and, when searching for Roman examples today, I came across several from the artworks of early Mesopotamian cultures, including this one below, from the Louvre.

|

| One of the many illustrations of a plinth type chair from the middle eastern cultures of the 2nd millennium BC |

After seeing a couple pictures like this on the internet I got out some of my books, and discovered that I had forgotten a lot about what I had previously studied. Back when I was in high school, I wondered what came before the classical art of the Greeks, and began studying Mycenaean, Minoan, and Sumerian cultures. Hmm, sounds a bit like my more recent approach to the early Middle ages...

As I was looking for Roman examples of this type of chair, and not finding many, I remembered having gone through this exercise a few years ago. What I find is that there are very few illustrations that clearly show this form of seat. There are several examples that could be, but nothing clear and definite. There are also lots of similar objects which have short legs or feet, so are not actually 'plinths' as technically defined (having a moulding 'round the base). At the same time, one does see many objects of this form, but they are altars, not chairs. I think, the last time I was doing this research, I came to the conclusion that, because a plinth chair and an altar had the same basic form, the artworks did not often depict people sitting on such objects. This is a highly conjectural conclusion, however, and would need a lot more research than I have given it, to draw any firm conclusion on the matter. Furthermore, in the Early Medieval period, many altars still retain this plinth form, yet the manuscripts also show seated figures on such objects.

|

| A plinth chair form, but this is an altar, not a chair. Roman, 3rd century from Wikipedia |

In the past three weeks, in preparation for this posting, I have gone through 7909 illustrations from medieval manuscripts, and separated out 723 illuminations which depict one or more of these plinth chairs. As I said, they are the single most common type of seating form, up until the beginning of the last century of the Middle Ages. These chairs are sometimes depicted in a detailed and realistic manner; at other times, they are quite abstract and it is even difficult to decipher exactly what the artist had in mind when he produced the illustration. In addition to the manuscripts, there are scores of relief sculptures, full figure ("in the round") sculpture, metalwork, ivory, and frescoes (as well as paintings after the 13th century) which depict this form of seat.

|

| Christ Enthroned on a plinth chair. note again the more simplified ornamentation of the chairs depicted in a smaller scale. |

One of the most elaborate depictions of this type of chair is pictured above; it comes from the west portal tympanum of the Collegiate Church of St Benoit Sur Loire, in France. The edge of the seat and the cove mouldings are completely covered in carved vegetal ornament; the side panels and base molding are further ornamented with pierced arcading. By contrast, one of the simplest depictions is pictured below. There are even more simplified drawings; simply a cube form, but this one retains the notion of a plinth, whereas a cube could represent anything, even simply a block of stone.

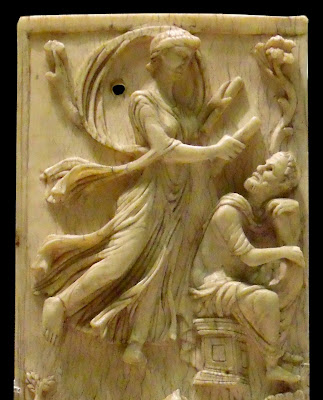

I have already mentioned a near complete lack of depictions of this chair form from the classical Roman Period, but by the onset of the Medieval Period, they have become quite common. I mentioned, in Part One of this article, that the Ashburnham Pentateuch has this form of chair, but, on studying it again, more carefully, it does not; the closest things to plinth chairs are objects like the one occupied by a king in the above illustration, or are of plinth form, but have a back crest with a drapery,(contrary to what I mistakenly said in the previous article). However, in the Louvre, and coming from roughly the same time period, (6th century) is a pair of ivory panels, which is known as the Nine Muses Diptych. (One panel of which is missing; there are only 6 muses pictured, the third panel, originally making it a triptych, has been lost.) In this ivory, there is a seated figure representing a poet. Interestingly, he looks very much like the figures in the evangelist portraits of many of the 8th and 9th century Gospel Books.

|

| A poet, attended by his muse, sits on a plinth chair from a 6th century Italian ivory panel, now in the Louvre. |

In the earliest part of the Middle Ages, this plinth chair had a very distinctive, 'plinth' form, but as the centuries wore on, and tastes changed, the chair took on other slightly altered forms as well; all in keeping with contemporary trends in design and taste. Discernable by the middle of the 10th century, a trend emerged, in which the chair had a layered or stacked appearance to it. This form seems to have reached its zenith by the middle of the 13th century, but by that time, another, almost chest-like form had come to supplant it. (As with most trends in furniture styles of the Middle Ages, one can find two centuries, or more, worth of overlap between these two ideas.)

|

| St John (recognised by his attribute, the eagle) 10th century Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt Early depiction of the layered effect |

Here is another example, from about 300 years later.

By contrast, this miniature, also from the same period as the last, shows a very simple straight-sided example with almost no overhang at all.

Of course this is somewhat of an over simplification of the topic, and only represents one variation which is a bit more pronounced than some others. In reality, there are scores of types, regional variations, and stylistic nuances unique to each artist. One could write an entire book for each century on the topic, but most people would, doubtless, find that extremely boring reading.

In short, however, these chairs could be rectangular, square, or even round; they were carved, painted, covered in gems, and imitation gems, metal foil, and moulded gesso. They could be of an enclosed box form, or be constructed of open arcading and tracery. They sometimes had short lips to retain their cushions, and often had very pronounced overhangs to the seat. Sometimes they took on purely sculpted forms, and in the 13th and 14th century, at least, could even have 'ears' or tree branch looking extensions coming from the rear corners. I have observed this in enough different artwork of two centuries, to realise this must have been a real fad, not just one artists whimsical notion.

|

| Madonna and Child, from the Met. I4th century Usually these sculptures are depicted in a frontal view so one never sees the chairs they sit on. 5 sides of an octagon with Gothic tracery |

Though I have just mentioned some less 'plinth-like' varieties that these chairs often took on, over and over through the centuries, we see other examples proving that the basic plinth form was extremely long lived, and never seems to have gone out of fashion, Although, based on a less frequent occurrence in the 15th century art, these chairs became less popular, they still seem to have sailed right on out the near end end of the Middle Ages. I have not spent a lot of time sifting through 15th century manuscripts, my searches usually stop with the 13th, nonetheless, I still have quite a few examples of this type of chair from as late as the later half of the 1400's.

|

| BL Harley MS 1340 fol 15r mid 15th century since this one is depicted as being made of stone, certainly no one can mistake it for a chest. |

Once one has grasped the notion that these types of chairs were quite prominent throughout the medieval world, the logical question to ask, is, "Why do none of them seem to have survived?" This is a valid question, and I ask the same. There is no simple answer, but there are several possibilities.

One must first realise that, compared to the amount of all types of furniture, there are very few examples of any of it still extant. The items which did survive were, for the most part, things which found further use, down the economic chain of society or were stashed away in an attic, or were of some value due to association with (or later attribution to) a famous person. Chests were useful as storage devices, but if these objects were not primarily storage intended, they may have been less useful to succeeding generations. Another factor to consider is that, many of these items, if built like the choir stalls which have survived, would have been made out of extremely thick material, rendering them much heavier than their size warranted.

Plinth chairs seem to have almost always been accompanied by a foot-rest and therefore the seat would have been higher than a modern chair. At some point, gradually, as with anything else, the fashion for sitting in an elevated chair with a foot-rest gave way, and most of the chairs that remained had their legs cut shorter to accommodate the changes in taste. It is not likely that this cutting down would have been very successful on a plinth chair, as its structure is entirely different to that of a chair with legs.

|

| Cassone associated with Guliano da Maiano late 15th century Is this a chest? I would have thought so, but perhaps it was originally a seat? |

Lastly, though we tend to call anything that is oblong, of roughly box shape, and made of wood, a 'chest', in fact, in the medieval mind, there were many varieties of furniture type; all having a roughly 'box-like' form. Though as a valuables safe, a refrigerator, a gun safe, and a set of file drawers are all more or less 'cabinet-shaped', most of us would not consider any of them to be furniture. In the same way, a chest for money, one for swords and armour, and one for traveling, were usually not 'furniture' in the Middle Ages, (though modern museum setting often display them in such a way as to give that impression). In the same way, something that might appear to us as a chest, might actually have originally been intended as a chair. Most medieval depictions of chests show them as either being smaller than chairs, or at the height as a table or buffet. Things that are more or less chair height, probably were originally for that purpose. (except for the numerous examples which have had their legs shortened due to taste and or rot, in succeeding centuries.)

Next time you are in a museum and see a "chest" which is missing its lower base moulding, and may or may not have a replaced top, but seems to be of seating height; consider weather or not you may in fact be looking at a plinth chair which, like its cousin the box chair, happens to have a convenient storage space in it as well.

It is a shame that some magnificent plinth chair from the 9th or 10th century (or any other) has not been handed down to us, and the best we can do is speculate and guess as to their actual appearance. Nonetheless, the artwork speaks clearly enough, to inform us that not all furniture of box form had a primary purpose as storage compartments. The items we lump together and loosely term 'chests' had many varieties of form and function. One of those forms was a plinth chair.

|

| BNF Fr 2608 fol 449v This looks to me a lot like the "chest" in the previous illustration. |

Next time you are in a museum and see a "chest" which is missing its lower base moulding, and may or may not have a replaced top, but seems to be of seating height; consider weather or not you may in fact be looking at a plinth chair which, like its cousin the box chair, happens to have a convenient storage space in it as well.

It is a shame that some magnificent plinth chair from the 9th or 10th century (or any other) has not been handed down to us, and the best we can do is speculate and guess as to their actual appearance. Nonetheless, the artwork speaks clearly enough, to inform us that not all furniture of box form had a primary purpose as storage compartments. The items we lump together and loosely term 'chests' had many varieties of form and function. One of those forms was a plinth chair.

Videre Scire

No comments:

Post a Comment